By: Chris Vandersluis

I originally wrote a version of this article for Microsoft’s TechNet site a number of years ago. The business of purchasing Enterprise Software has unfortunately not changed much in the meantime so the lesson bears repeating in this updated version.

It happens around here all the time. A client sends a “Request for Proposal” (RFP) to the office with instructions to complete a response in a few days or week and send it back to have our enterprise system considered for purchase. RFP’s pretty much all look the same. There’s usually a brief overview, instructions on what you need to do to have your response be considered including how it needs to be formatted and when to send it back etc. Then there’s a long grid of features that are required and a number of additional essay questions to write answers to.

The challenge with RFPs is that they aren’t ideally suited for selecting enterprise software and process that ensues when an RFP process is followed doesn’t guarantee the best decisions for the organization. RFPs were designed by the purchasing community as a way to get the best commodity at the best price and they still do a great job of that. When the offerings are comparable then the decision making process can focus on the best price with only one or two additional variables (such as shipping dates) to contend with. When the possible solutions are in the same general category but not at all comparable (As is the case with Enterprise Software) then the number of variables that must be considered by purchasers is huge and the RFP process doesn’t add value to the selection.

How most companies select enterprise software

Let’s start by looking at the the most typical process that occurs on a regular basis with any software vendor or solutions provider of enterprise software. I’ll be talking about enterprise project management software or enterprise timesheet software as that’s what my firm provides but the paradigm is the same for virtually any enterprise system selection.

In most organizations, the impetus to look for enterprise software comes from some problem. Perhaps the problem is surfaced by the field personnel. Perhaps the problem is identified by someone in senior management. However it happens, the initiative has to get support from someone in senior management. The idea that grass roots selection of a system that will impact the entire enterprise is extremely rare even in the most progressive of organizations. So, most typically, a senior manager decides, “we need to purchase this kind of enterprise system to fix our problem.”

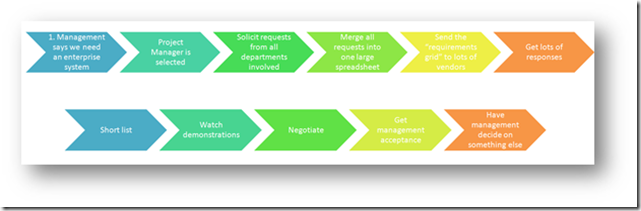

Typical Enterprise Software Selection Process

A project manager for the selection effort is volunteered. He or she does what we all do. They go to the Internet, load up a search engine and type in “EPM Software” (or whatever enterprise system they’re looking for). Immediately a half-million hits are returned. A diligent project manager might investigate the first dozen or so educating themselves on what kind of systems might be available before moving on. A less diligent researcher will look at the top one or two. Clearly no one has the time to surf through a half-million or more hits to see if the very last one might be the ideal system for the organization so successful search engine optimization by vendors counts a lot in the selection process.

Undaunted, the project manager now assembles a selection committee from among those who will be affected by the implementation of this new enterprise system. Some of those on the committee may be from among field personnel who originally identified the need in the organization in the first place. Others may not. There may be a mix of people on this selection committee who have diverse interests and incentives in what kind of system will be selected.

The hapless project manager now solicits each member of the committee to poll their representative group for what they require in the new enterprise system. How does each committee representative do this? Well, first of all, not everyone puts in the same effort but for those who do their homework, they ask their staff to submit a list of features that they would find important. Then they too hit the Internet and surf some vendor websites. They can copy and paste from features they see in the brochures of these sites as each site gives them new ideas of what kinds of requests they might be able to make of a new system.

Now the committee is re-assembled and the long spreadsheets of each committee member is merged into one massive spreadsheet. The mega-spreadsheet of requirements is categorized but there are challenges. First of all the diverse needs of the committee now becomes more apparent as features are requested from the wide range of perspectives and desires. There may be committee members in different departments but also in different divisions or even different countries. There is almost always at least one request which is at conflict with another request in the same list (e.g. the system should be very easy and not have many prompts and the system should be very flexible with a large number of options for each user).

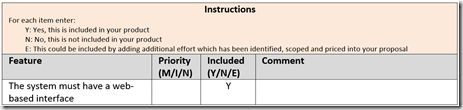

Finally the combined spreadsheet that the vendors will see is complete. It has hundreds of feature requests and for each one the vendor will be expected to say “Yes”, “No” or “Yes with some effort”. A  weighting system may be also attached to say whether this feature is a “Must-have”, an “Important-to-have” or a “Nice-to-have”.

weighting system may be also attached to say whether this feature is a “Must-have”, an “Important-to-have” or a “Nice-to-have”.

The RFP is almost ready to go. There will be a few essay questions usually about the technical architecture of the selection and, depending on how many people were polled about these requirements, the architecture requests can be equally conflicted. (e.g. The system must have all data stored centrally in the SQL database and the system must allow any data to be stored in a distributed fashion locally on the user’s computer).

Actually, it’s sounding pretty good so far, don’t you think? After all, we’re going to get back a bunch of vendor responses that show who can deliver all the features that we’ll need.

But there’s actually a fundamental problem with what I’ve described thus far. A problem that doesn’t occur when we’re using the RFP process for a commodity rather than an enterprise system.

The problem is this: An enterprise system is a solution to something. But we’ve said nothing so far about the problem. Having now said it out loud, it might seem obvious yet it is almost universally common in RFPs to not explain the original problem that started the initiative in the first place. This is such a common occurrence that the technology industry has come to accept it as normal and acceptable.

Why selecting enterprise software that way doesn’t work

Purchasers have been using this method for decades and no one questions it, but people in the enterprise software business know there is a fundamental problem with the classic RFP method of selecting enterprise software.

First of all, just because you have an enormously long list of features, it does not necessarily mean that you are any closer to solving a business problem. In fact, if you haven’t even articulated what specific business problems you are trying to solve then you are likely to make things more complex and ultimately worse, not better. The RFP process was designed to purchase commodities. When we’ve got homogeneous products like shoes or potatoes or sugar, then purchasing these items in this way can result in the lowest cost bidder and the best selection from among the possible suppliers. The responses to an RFP for a similar commodity makes comparing possible suppliers very easy. When the variables for each product in the mix are infinite (as they are with enterprise software) then the responses to the RFP have an infinite number of variables also and the process yields results that have little value.

When we use the RFP method of selecting enterprise systems, the RFPs mostly all look the same. This is because they are all created in response to the same stimulus. The project manager requests a list of ‘what you will need in this enterprise system’ and the only vocabulary most middle managers have to respond to that request is a list of features. Consequently, the responses to RFPs all look the same. They’re a checklist of all the features available either as part of the system or as part of the system with some effort.

What is most common for selection teams is that they will receive a number of responses to their RFPs, they’ll wade through the hundreds of pages and, when they’re finished, they won’t feel any closer to a solution than when they started. This is terribly frustrating for purchasers who put in enormous effort in creating what should be a fair request for proposal and in evaluating the answers only to find that the exercise was for naught.

Worse than all of this is that experienced enterprise salespeople know the process will yield frustrating results and are at work from the moment they hear there will be an RFP created. They’re not working on the RFP response. That’s not relevant. Instead, they are working two or three levels higher in the management structure, looking for the original impetus that got the RFP started. They look for the senior executive who articulated some business challenge and set the wheels in motion so that purchasers and other middle-management staff would ultimately create the RFP and send it out to vendors.

When the RFP responses end up without a clear answer to the business problems that are almost never articulated within such a purchasing process, the enterprise salesperson is ready to leap into action, and will attempt to have a senior executive bypass the process altogether and select a system based on their own personal relationship with the senior enterprise salesperson rather than the score on the spreadsheet.

If you think this sounds jaded, you’re wrong. In fact, it is extremely common.

But what about a Proof of Concept or Pilot?

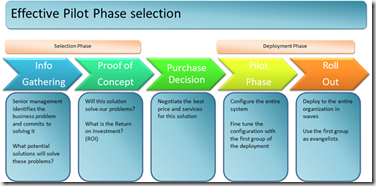

So, we know the classic purchasing process is flawed when we apply it to the purchase of enterprise software. If that’s the case, how should we choose enterprise software such as an enterprise project management system? A popular method is to use the Proof of Concept or Pilot Phase method.

These two terms are often used synonymously so let’s start off by talking about what is a Proof of Concept or a Pilot deployment.

Proof of Concept

In a Proof of Concept the prospective organization deploys the enterprise software in a limited fashion in order to prove that it can accomplish a technical challenge where there is some question as to the solution’s ability to overcome that challenge. An example might be for data volume. “We’re concerned that the product might not be able to handle as many tasks as we have per project. We’d like you to come with the software, take 2 or 3 example projects with 500 tasks each and show us how these can be loaded into to the software and that the software can still perform its basic functions with this volume in it.”

Pilot Phase

A Pilot Phase is an installation of the enterprise software but with a limited scope. A pilot deployment might be for a subset of users; for example only 10 out of 1000 people will use the software fully for a 4 week period. Or, it might be for a subsection of the functionality or a subset of the volume of data; for example only 10 out of 500 projects will be loaded.

How is the Proof of Concept or Pilot Phase used?

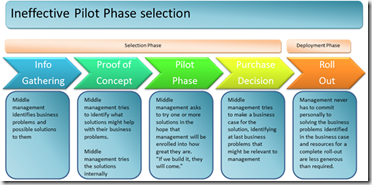

The problem that is often encountered is how the Pilot Phase or Proof of Concept is applied. It is quite rare when a prospective organization calls and asks us for a Proof of Concept proposal that they can identify what technical concept needs to be proven. “What technical concept are you hoping to prove and how will we be able to measure that we’ve proven it?” we ask.

What is more common is that someone in middle management has identified a piece of enterprise software that they hope will make their lives easier in their organization. Senior management is not at all involved and, the middle management staff  have not even articulated what business challenges they are trying to overcome. It is their hope that if the solution was just in the building, that the next time someone from management would wander down the corridor, they would see the solution in operation and would instantly give their blessing to an enterprise deployment. To coin a term from the movie Field of Dreams, ”If we build it, they will come.”

have not even articulated what business challenges they are trying to overcome. It is their hope that if the solution was just in the building, that the next time someone from management would wander down the corridor, they would see the solution in operation and would instantly give their blessing to an enterprise deployment. To coin a term from the movie Field of Dreams, ”If we build it, they will come.”

Getting management support for a solution in this manner is rarely successful. The problem with enterprise software is that we need senior management’s involvement to make the deployment a success. It is senior management who will be the ‘clients’ of the reports and analysis from this enterprise system. It is senior management who will need to invest personally to allow a range of staff the time required to design, configure and be trained in the enterprise software. It is senior management who will have to accept or even help redesign the business processes that are part of any enterprise system deployment. Without senior management giving not just their blessing but also their implicit support and direct assistance, no proof of concept will help.

This is true also for a pilot phase. If the company has not committed from the highest level to solving some business problem through the use of enterprise software,  then the introduction of a pilot phase is not productive.

then the introduction of a pilot phase is not productive.

This is not to say that pilot phases of a deployment have no place. They do carry a critical spot in a successful deployment. That place is immediately after the purchase decision is complete and the design of the enterprise system has been concluded. Now a pilot phase makes a great place to test out our enterprise system design and fine tune it for general deployment.

It is only when a pilot phase is done in the hope that seeing the software in action will result in management selecting it,that we create an ineffective Pilot and get no further ahead in the selection process.

How should organizations select enterprise software?

Enterprise systems are purchased by middle to large sized organizations every day and, while the RFP method may not be the most effective, there are several methods of selecting enterprise software such as Enterprise Project Management or Timesheet software that is very effective. Here are a few tips for creating your own effective enterprise selection process.

1: Articulate the Problem

First and foremost, articulate the problem. This means that senior management must be involved and the problem to articulate is a business problem so it should be articulated in business terms. One good question to ask is, “What business decision can we not make now or can we make only with great difficulty, the making of which could be eased with the deployment of this enterprise system solution?”

There may be a series of business challenges that you wish to solve with the use of this enterprise system.

2: Give Vendors some latitude to create the solution

Once the business problem or problems have been articulated, contact possible vendors in and make sure the access to the senior management who assisted in the process thus are is transparent. “Secret” vendor meetings with senior management become impossible when management is part of the process from the beginning. Let the vendors understand the problem and give them some latitude in answering it. You may find out more about your organization in explaining how these business challenges affect you than you realize and you will certainly see a much wider range of possible solutions to your problem when you don’t try to describe the solution to the potential vendors.

When you talk to possible solution providers, make sure they understand that they must speak to both the technology and the business process challenge. There has never been enterprise system solution that didn’t have some impact on the organization’s process. If the solution provider can’t help with how the process will be impacted, then you’re only looking at part of the solution.

3: Go meet some people

When you get down to a couple of possible solution providers, ask to talk to some of their existing clients. Even better, see if the vendor will let you go visit some of their existing clients. Good solution providers often have clients who have had success in their own deployments and who are generous enough to make time to meet prospective clients.

You’ll learn more from a couple of hours with an experienced client of the possible solution than you would have ever learned from reading RFP responses or looking at vendor sales demonstrations. When you ask the vendor for possible client references and site visits, you might think the ideal company to meet would be one exactly like yours. That’s not always the case. It’s often extremely valuable to meet companies in other industries that are related or somewhat similar to yours. You might also learn lots from organizations who are bigger or smaller than you are. Place more emphasis on how much experience the site visit organization has had with the solution rather than what version they’re using or whether they’re of the exact size or in the exact industry you’re in.

If you are lucky enough to visit an existing client, remember that they’re not the vendor. Be respectful and courteous and thankful. Bringing a small gift, perhaps of company logo promotional material is often well appreciated. While you’re with the organization or while talking to references on the phone, some possible questions might include:

- What process did you use to select this solution over others?

- What impact has this solution had on your business processes?

- What was the most challenging aspect of the deployment?

- What was the most valuable return on investment thus far?

- How do you see the solution evolving from here?

Don’t expect only happy answers.

A vendor who is completely unable to provide references has to be somewhat more suspect than one who has a number of satisfied clients.

Finally, when you’ve made your selection, deploy in phases. You can find other articles in the blog on how to deploy in a phased vs. big-bang mode. This will mitigate the risks involved in any enterprise system deployment and help fine tune the deployment process as the system evolves.

Remember that any enterprise system deployment is a dynamic process. It’s not a one-time decision with happy results arriving month after month forevermore. The most successful enterprise deployments start from a selection that involves the key personnel who will be a part of the deployment process from the most senior in management to the most tactical in the field and continues through the evolution of the system in phase after phase.

An effective enterprise system selection is only the first phase of the process.