When under pressure, we all tend to retreat to that which is familiar. That’s not just in project management.

It’s true everywhere.

I’ve been studying a bit of Abraham Maslow thanks to some other ideas I’ve been working on associated to Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs”. In 1966, he was quoted in the Psychology of Science as saying “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” The expression however, goes back much further.

The British saying a “Birmingham Screwdriver” refers to a hammer but more broadly means you’re using a tool for purposes other than what was intended.

When we apply this syndrome to modern business it’s not hard to find examples. In my own company HMS Software, I’ve got to stay on alert with my technical experts. At HMS we use the same people for development as we do for technical support and for deployment assistance. They’re all top notch programmers and as such, every technical problem they tend to encounter is seen through the lens of a top notch programmer. “We could code that,” is a common response to a business challenge.

We’ve had to coach our staff in starting with answering the question “Should we do it at all?” and then “Can this problem be overcome by existing code?” This doesn’t always make the programmer/deployers the happiest. They’d be much happier I think if I just let them write code whenever they encounter a technical challenge. But, sometimes writing new code for any request isn’t the best for either the client or the company.

When we look at this same phenomenon in the project management world, we start to see how different the perspectives of those engaged in project management can be. Let’s take a look at several perspectives and then see how this is playing out in real life with some of our clients right now. Let’s imagine three different people in a organization, each with very different jobs.

Strategic perspective of an executive

We’ll start with the Chief Information Officer. Their responsibilities include making sure IT projects are all on track of course, but it’s unlikely that they’re working on that every day. The CIO has to be looking at the organization more strategically. That includes looking forward to next year’s budget, looking at staffing levels, should they hire or outsource? What about remote work policies? What about security? What about a SOC II audit? What about innovation and R&D? What about new products? What about internal infrastructure? Should they maintain internal data centers or move infrastructure to the Cloud?

A CIO has a huge vested interest in project management but it isn’t task-by-task. The tool a CIO is most likely to use? Excel.

“What about a barchart?” you say.

Not so much. If a barchart is even presented, it’ll likely be migrated into a spreadsheet.

CIO’s are most likely to ask for high level performance indicator barcharts. I once had a CIO of a rather large organization ask me about a project dashboard. I flipped through a couple of examples of screenshots on my laptop and his eyes went wide, like a cat’s do when there’s a new shiny toy.

“Could we get that?” he asked quietly.

“Sure,” I said.

“Um, when?” he asked.

“Friday,” I said.

“Really?!” he asked.

“Well, no. I mean, one Friday someday but not instantly, no,” I replied to his immense disappointment. “A dashboard is more than making some graphics on a screen, it’s data that’s got to be validated. It’s a process and, yes, it’s some graphics on a screen. It will take weeks probably to have something you could make a decision from.”

He got his dashboard in the end several weeks later but it taught me that even senior managers can be enthralled by the temptation of a shiny object.

So with C-level executives, looking at what tools they commonly use is most important to project system deployments. What we’ve seen in the past is we take tools that we like from our own perspective as a project manage and think that the C-level executives aren’t using a barchart with capacity planning only because we haven’t trained them.

Not true.

Even C-level executives who come from a history of being a project scheduler, don’t use those tools day-to-day once they become that CIO or CFO or CEO. They tend to use tools that are appropriate to their perspective.

Operational perspective of a project scheduler

Ok, let’s think about our project and resource managers working at an operational level. These are the people we would have once said were the only people interested in project management. When we talked about project management and project management systems in the 1980s we were typically referring to project schedulers. Focus was on concepts like the Critical Path Method and a mix of bar chart and network diagrams.

When we think of modern day concepts of project management the term is ubiquitous. Everyone is taught about some kind of project management from elementary school through university regardless of your educational focus.

There is still, however that need for a middle management type working on scheduling, estimating, job costing, resource levelling and project reporting. That person may be part of a project management office or might work apart but there is a critical role for the person in the middle range of this spectrum. The person who can take a strategic plan with a half dozen work categories and expand it to an actual project based in time with estimates for effort and costs.

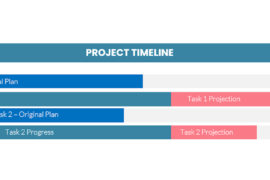

In this middle perspective, the most common visual tool is the barchart. It allows tasks to be created in a hierarchical fashion and then sequenced where possible and the effort expected within each task. The end result is a schedule which can be refined both from above by constraint and from below by detail.

A project manager isn’t looking at next year’s budget or whether to hire or fire. In fact, the irony of most project management roles is that the project manager has a lot of responsibility but very little authority. So, the role is a lot about reporting, analyzing and encouraging the end result. So a project manager is more likely to be using barcharts, PowerPoints and perhaps even spreadsheets for communications. They’re very unlikely to need Agile boards to manage day to day task accomplishments.

Tactical perspective of a team member

Let’s go from managers to the members of a team or even a team lead or scrum master. If you’re working in an Agile type of environment then a team member will have a very short project management time perspective. They aren’t looking at the ‘big picture’. They may not even care about it. Just tell them what they need to work on for now and they’ll get to it to the best of their abilities. For technical types of projects that are most often thought of in a project management context, An Agile approach is becoming most popular.

A tactical team member needs a list of what you’d like them to work on today. Any list will do. It should be filled only with things that can be accomplished in a short period of time, perhaps a week or even two. Tasks of no more than 2-3 days are best. Then, links to whatever documentation and source materials will be the next most interesting thing. As soon as a task is complete, they will want to mark it as done and off their list so they can move on to the nest task. Reporting is as simple as “did you finish that, yes or no?” In some cases the effort on a task will be important but at this level it is not always reported in such detail.

Working at a team member level, tasks aren’t even really rooted in a time scale. The team member takes a task off a list for this period (this week for example) and then works on completing it. The concept of Agile Boards is popular at this level. Whether it is sticky notes on a white board or a software system, the visual concept of grabbing a task and dragging it to you or passing it along to a completed column is appealing here.

TimeControl Project Project Management

AT HMS we’ve recently released TimeControl Project, a premium subscription version of our TimeControl timesheet system. TimeControl Project starts with the concept that the perspective of one type of person about project management may be quite different from another type. The system has tools, data and analysis that are tailored for each of the three levels we’re discussing. So, spreadsheet views for executives and barchart views for project managers and resource capacity histograms for resource managers and board views for team leads, scrum masters or team members.

It has been fascinating within our own sales and technical staff to see their own approach to our own product. For the developers who are team members, they are drawn to the board concept. Their innovation on that functionality has been highly focused. But, they are not interested in the spreadsheet views or the barchart views with quite the same passion. Our senior account managers have been highly interested in the barchart views. They are most likely to serve as project managers in our office. At the management level here, the spreadsheet view is the most used. The ability to have the spreadsheet automatically populated with actuals and then use the more traditional formulas and format for projections is ideal from that perspective.

This was an issue all throughout the design and coding of the product. Only constant communications between the different levels of the company kept bringing us back to our original concept of being able to have multiple perspectives inside the same product but keeping the needs of each perspective distinct.

As we’ve presented TimeControl Project to our clients, its reception makes my point. Some users focus on one aspect, other users focus on another. There’s very little conversation of how the different tools at different levels all integrate their data. The users expect what they’re seeing to be tied together but they expect it to be separate. The concept that we’d started with has been completely validated by external user response.

It’s all together – so it’s all integrated, right?

Not necessarily.

One thing that became apparent to us in working with existing clients over the years is that not only the perspective of each part of the organization is distinct but there is a decided desire to keep the data separate also. For the last 20 years or so in project management software industry has pitched the idea of everything being all tied together.

It’s a great demonstration but not as easy a deployment.

In the demonstration, senior executives are shown how the smallest change in every end user’s task ripples upwards to become a small change in an executive level dynamic view. It’s a shiny object for executives who imagine they will be able to exert some new level of control and oversight but the challenge of delivering this dream is not trivial.

As I’ve said many times, it’s not the technology that’s a challenge, it’s the process. To deliver on an all-integrated project management system, we’ve had to combat promises and expectations of things like real-time project management and, management through to user decision making.

It’s certainly possible to create an all-integrated project management system but the end result isn’t as simple. There still needs to be process. There still needs to be approvals of the data and there still needs to be a careful management of where the data is going and how it’s validated.

The most common result is that the different levels of the organization keep their own tools and keep their data separate.

So being able to integrate data when it’s appropriate and keep the data separate when that’s better is exactly what makes the organization most effective.

In the end if there is understanding from users at each level of the project management process that they don’t have the only perspective, everyone can benefit.